The Moviegoer is the diary of a local film buff, collecting the best of what Chicago’s independent and underground film scene has to offer.

Apologies for not writing a column last week—consider this a two-week catch-up, one informed by a stretch of particularly immersive (and in some cases contradictory) viewings. In fact, the past couple weeks have reminded me of cinema’s capacity to withhold, offer, and defy clarity. Sometimes, you watch a film and walk away with a new understanding; other times, you leave with more questions than answers.

Further researching Trinh T. Minh-ha’s What About China? (2022), which screened two weeks ago as part of Conversations at the Edge at the Gene Siskel Film Center—and at which the revered Vietnamese filmmaker was present—I came across a synopsis (on IMDb of all places) that calls it “a hugely imaginative cultural critique of China that resists the idea of a single historical narrative, instead evoking the plurality of indigenous perspectives.” I’m not usually one for parroting summaries, but the above very neatly describes an otherwise ethereal, poetic film that lingers in my mind even as it actively defies interpretation.

Perhaps my least favorite part of writing about movies is when I have to summarize the film in question. I find it limiting, trying to reduce something so expansive to a few neatly digestible lines. Yet sometimes I also find myself relying on those very synopses—especially when writing days after seeing something, struggling to recall its shape, its movement, or even its mood. In this case, the description opened up space for me to think about the film as a kind of refusal: a refusal of conventional documentary narration, of the ethnographic gaze, of the idea that a nation or culture can be made legible through images alone. What About China? lingers in the mind like an impression or a question one hasn’t yet figured out how to ask.

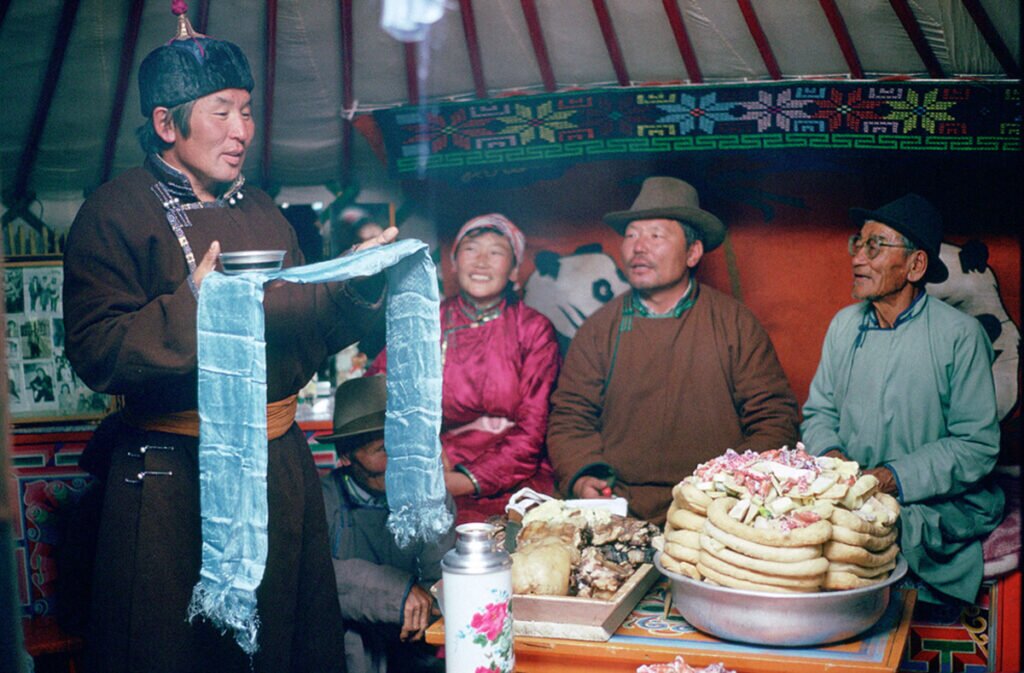

By contrast, Ulrike Ottinger’s Taiga (1992)—which I saw over the span of three days at Doc Films at the University of Chicago—is almost shockingly direct, at least in its structure and duration. The nearly nine-hour documentary depicts the taiga region in northern Mongolia and the nomadic Tsaatan people who live and move through it. Split into manageable chunks, the film never once felt like a slog. It’s purely the stuff of life: daily rituals, long silences, quiet moments of work or rest, the wind. It too resists narrative in the traditional sense, but not in a way that obscures or elides. Instead, it quietly insists on presence—ours, theirs, Ottinger’s. Watching it, one feels not so much transported as returned to something elemental, tactile, real.

More recently, I saw a double screening of Shohei Imamura’s Ballad of Narayama (1983) and Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles (1974), also at Doc. It’s a pairing that feels hilariously unhinged on paper—brutalist folklore followed by anarchic and somewhat dated satire—but maybe it’s exactly right. Both are transgressive in their own way, confronting social mores through exaggeration, absurdity, and an element of formal control. Why not let them sit side by side? Cinema contains multitudes.

Until next time, moviegoers.