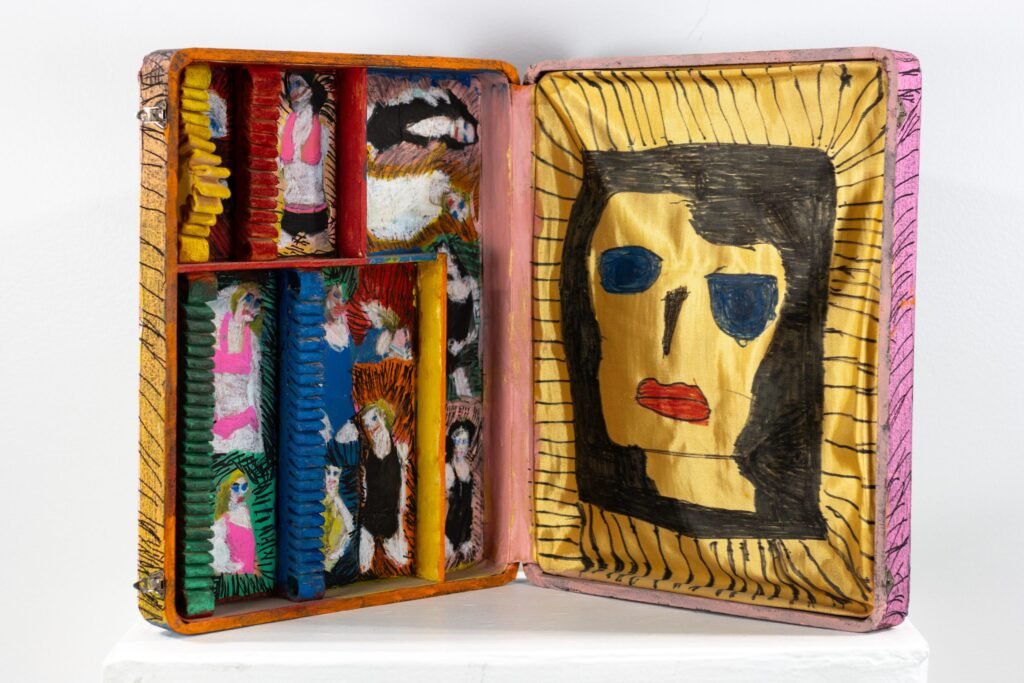

An artist in paint-splattered black clothes puts the finishing touches on a busy, vibrant acrylic scene on an oversize canvas. Nearby another artist—a face mask tucked beneath her chin—leans over a comic-like illustration, carefully coloring in the black outlined drawing with green marker. At another group of tables, an artist is cutting up pieces of cardboard for use in a sculpture while a colleague to his right finishes up a pristine marker illustration featuring saturated blocks of green, yellow, orange, and gray. Other artists mill about the studio; some are wrapping up pieces or preserving the day’s work on their storage shelves.

It’s a typical Monday afternoon at the West Town location of Arts of Life (AoL), a progressive art studio founded 25 years ago. The bustling space exemplifies Arts of Life’s simple yet visionary mission: to provide artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities “a collective space to expand their practice and strengthen their leadership.” Here, artists have the autonomy to make the work they want to make, to develop their artistic voices and creative practices alongside their peers, and to further their careers through a number of professional opportunities. All decisions are made collectively, and the program is open to all applicants, whether or not they have previous artmaking experience.

“What they said”

3/28-5/9: by appointment Mon–Fri, 10 AM–3 PM, circlecontemporary@artsoflife.org, Circle Contemporary, 2010 W. Carroll, artsoflife.org/event/what-they-said

“Arts of Life: 25th Anniversary Retrospective”

8/11-9/30: open daily 10 AM–5 PM, Design Museum of Chicago, 72 E. Randolph, designchicago.org/arts-of-life-25th-anniversary, free

Arts of Life annual benefit auction

10/3 Epiphany Center for the Arts, 210 S. Ashland, more info at artsoflife.org/25th

“A lot of what we’re trying to do is to help the artists just have confidence in their own ideas,” said Tim Ortiz, AoL’s program director. “They’re not taught that in other places. And people in this population—they don’t learn to spend time on things that are their own. That’s what’s different here. . . . A lot of what we do is just encourage people to try. We try to notice what their interests are creatively and help them to take those things further.”

Founded in 2000, AoL is a beacon of joy in the largely underfunded, and at times abusive, landscape of disability services in Illinois—a state that consistently receives low marks for its efforts to serve people with disabilities. AoL is the first, and still the only, state-licensed community day program in Illinois with a focus on artistic career opportunities for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The organization is celebrating its 25th anniversary through a yearlong series of programming, which kicked off February 22 with a party and a book launch for 2wenty-5ive, a beautifully designed hardcover that tells the history of AoL and highlights the practices of 25 of its artists.

Credit: Kirk Williamson

As Nik Heusman, a longtime AoL artist, says about the importance of the organization in 2wenty-5ive: “I can come here and let my hair down and just go to town on art. I want to get my art out there into the world. I want people to see me as a person instead as a person with a disability. I want them to see that a person who has vision problems can accomplish anything in the world.”

Arts of Life’s collaborative, artist-centric model dates back to its very beginning. In the late 90s, cofounder and executive director Denise Fisher was working in residential services for adults with developmental disabilities in Chicago’s north suburbs. Through that work, Fisher became friends with her neighbor Veronica “Ronnie” Cuculich, one of the residents and a lifelong maker. Cuculich and other residents had found relief working on art projects at home. When the agency Fisher was working for was slated to be absorbed by a bigger one, it felt like the perfect time to pitch a new project: a day program devoted to making art. “I went and talked to families that I knew in the organization, and found other people that were interested,” Fisher said.

They began working on the project in 1999 and, in 2000, opened the first location, on West Grand. (It was founded by Cuculich, Fisher, and a colleague along with nine additional artists; Cuculich died in 2010.) “In the early days, we were just kind of putting it together,” Fisher said. “We were small enough that I would meet with all the artists weekly and kind of just ask open-ended questions about what they wanted.”

Credit: Kirk Williamson

This is how AoL’s four core values—inspiring artistic expression, building community, promoting self-respect, and developing independence—were formed. After a year, the staff looked at the data from those conversations and realized these were the things people were consistently bringing to their attention. “A lot of the people early on had institutional backgrounds,” Fisher said. The artists often didn’t feel like their peers were that helpful “because they had come from institutional settings where really the staff had all the power.” So in the early years, the organization worked to undo those dynamics, getting artists to collaborate.

“Once that was set, we started to realize that what we were talking about more often was integrating the broader arts community, that our artists were in the kind of ‘outsider’ label that’s inappropriate and really dated,” Fisher said. (The term “outsider artist” typically refers to someone with no formal art training and little to no influence from the mainstream art world, but it has fallen out of use in recent years as a needless and outdated categorization.) The organization reenvisioned its mission statement to build in leadership and development in the art sector.

From serving ten artists in one studio space, AoL has grown to serve over 60 artists across three studios (in West Town, Woodlawn, and Glenview), alongside integrated community classes at Evanston Art Center and the Art Center Highland Park and an in-home support program. (Approximately 150 artists have worked at AoL since its inception.) In 2017, the organization launched the Artist Enterprise Program, a professional development arc that allows artists to opt in to the vocational tracks of maker, curator, educator, or career, and also works to expand professional opportunities to exhibit and sell work. While artists at AoL do pay a fee—most pay through a Medicaid waiver program though some pay out of pocket—they also receive a monthly stipend based on their attendance and 60 percent of revenue from any works sold.

In the past several years, AoL has begun bringing artwork to art fairs around the world, from EXPO Chicago to New York’s Outsider Art Fair to Art Fair Tokyo. Around seven exhibitions per year are held in AoL’s Circle Contemporary gallery, housed inside its West Town location. Featuring both AoL artists and artists from the greater art world, the exhibitions are put together by guest curators and artists from the organization’s curatorial committee. (The next big event for AoL’s anniversary programming is a group art exhibition, called “What they said,” opening Friday, March 28, at AoL’s Circle Contemporary gallery and cocurated by Nick Cave and Bob Faust.)

AoL artists are often invited to show at other galleries or institutions, such as the 2023 Intuit Art Museum exhibition, “Hand Drawn Circle: Arts of Life studio past and present.” That same year, Ruschman gallery hosted a solo exhibition of work by AoL artist Susan Pasowicz, who has been a studio member since 2013. Eric Ruschman first got to know Pasowicz when he was organizing a 2019 Circle Contemporary show called “All Well and Good” with her and fellow AoL artist Tim Stone. The title stems from a conversation Ruschman had about the show with Pasowicz, where she asked him (a fervent admirer of bright colors, or “my wheelhouse,” as he describes it): “Well, color is all well and good, but what about a gray show? With a disco ball in the middle?” Though that ultimately wasn’t the exhibition Ruschman put together, he was struck by Pasowicz’s energy and talent.

Courtesy Arts of Life

“I just am really drawn to—and this is deeply embedded in her work, as well as her personality—that she is capable of holding all of this like candy-coated joy, Hello Kitty sunshine-like stuff alongside something that’s darker, something that’s a bit more mysterious,” Ruschman said. This shows up in Pasowicz’s gorgeous, time-intensive colored pencil drawings, made by making layers upon layers of marks. The result is often a subtle gradient of pastel colors, sometimes with a black floating orb in their midst.

Some of those marks are made by tracing a Slinky over and over again, an ingenious technique that Pasowicz told me was “just an idea.” “You could do it with other things, like a square. . . . Doesn’t really have to be a Slinky. Just an idea in my head that I made.”

Ruschman has sold some of Pasowicz’s work to collectors and praises AoL for working to get her art seen outside of the city, a “necessary next step for Sue’s practice.”

When I visited Arts of Life, it was the first appreciably nice day of late winter, and the weather made the mood feel extra buoyant. Many of the artists were eager to share their work with me. Rocco DiCaro, who joined AoL in 2023, showed me Emily! (and Jerry and Lucy): Emily’s Family Fun Tales, a book of hand-drawn comics that he laid out himself and self-published through Amazon. It features 15 stories about a little girl named Emily and her family and friends. “It’s kind of in the style of Peanuts,” DiCaro told me, adding that he’s at work on a second volume.

Photos by Kirk Williamson

While we were chatting, his tablemate Stefan Harhaj chimed in to boast about DiCaro’s YouTube drawing channel, which shows how he makes his comics. I was familiar with Harhaj’s work from 2wenty-5ive; his drawings and paintings have a folk art aesthetic, often depicting the natural world or simple, repetitive abstractions. Now he mostly makes sculptures.

Also working at their table was William Lilly, who works primarily in marker, so as to not mar his impeccable clothing. The charming artist—also known as “Shotgun Lilly” due to his preference for the front seat—is a devotee of metal; he implored me to check out the song “Carrie” by the band Europe, as well as the ballad “Truth” by Godsmack. Music inspires his artwork—many pieces feature the names of his favorite bands—as do tornadoes.

Tatianna Adams brought me around the studio to view her cardboard sculptures, including one featuring all the Arts of Life artists. At the top of the diorama-like piece, a sign reads, “Arts of Life come do your artwork here.” Her latest work was in honor of the organization’s recent trip to New York City, where they had a booth at Outsider Art Fair and a book launch party at Soho House. The sculpture had a background of apples, printed from the Internet, with a rectangular block mounted on a waterlike base featuring the Statue of Liberty. Overlaid over the water were the words: Arts of Life takes New York.

Courtesy Arts of Life

Courtesy Arts of Life

What was clear after talking to these artists was that they take their practice seriously and that they value the time they spend at Arts of Life. “It’s a way to express yourself, and I like drawing, I like painting,” artist Alysha Kostelny said about coming to Arts of Life. Lilly told me he likes “the people and the art.” Adams used to draw before coming to AoL, but said, about her cardboard works, “This is better art.” In a written statement, North Shore studio artist Ariée Carter wrote, “I love being part of AoL because they are my third family.”

“When our artists define the nature of their work, including its success, they will have just as much to offer as any other person, and just as much chance of doing great things,” Ortiz writes in 2wenty-5ive, an apt summation of the organization’s overriding ethos. “This is validated in our studios every day.”