Boston Marathon

Finnish champion Eino Oksanen joked about having the offending canine shot, but Johnny Kelley defended the “happy, spirited dog.”

Though the 1961 Boston Marathon stands out in history for multiple factors — including the rare and jarring presence of snow flurries, as well as the dramatic duel between champions John J. Kelley and Eino Oksanen — the most conspicuous part of its history revolves around a mysterious dog.

Headlines the following day conveyed a pithy picture.

“Dog, Oksanen Down Kelley,” declared The Boston Globe’s sports page.

“Kelley Spilled by Dog,” read The Boston Herald.

In an era before fences along the side of the route were ubiquitous, the presence of a dog could have a major impact on a high-level race. And that’s exactly what happened in 1961, though it’s (human) protagonist never wavered from gallantly arguing that the dog had no impact on the ultimate result.

In fact, the bizarre incident inspired an ironic outcome: The race’s winner arguably emerged as the least heroic of the podium finishers, even as he stamped his authority on the final mile with a dominant finishing kick.

The hyped rematch

Ahead of the (then) annual April 19 marathon race date, the competition between Kelley and Oksanen deservedly drew much of the focus.

Kelley, 30, and Oksanen, 29, had dueled before, with the Finn winning the earlier race in 1959. Kelley, known as “Kelley the Younger” (to differentiate him with John A. Kelley, winner of Boston in 1935 and 1945), had triumphed in 1957 in his own right.

Both were considered to be at their peak, and looked expectantly at the chance to be crowned with another wreath at the finish line.

It was also the continuation of a still relatively new dynamic in Boston: international winners. Prior to 1946, there had only been two non-North American champions. But starting with Greece’s Stylianos Kyriakides in ’46, international runners won in Boston every year with the exception of Kelley in ’57.

“Kel vs. the Finns,” summarized Globe columnist Jerry Nason. Oksanen, a detective in his day job, was one of several Finnish distance runners who dominated the era (the Scandinavian nation won six of nine Boston Marathons between 1954 and 1962).

Kelley, a Connecticut high school English teacher, was the local favorite.

A “floppy-eared, mongrel dog”

Conditions on the day of the marathon were notable for being unusually cold and wintry. Snow flurries, a relatively rare sight for the Boston Marathon, made the already difficult journey from Hopkinton even tougher for the field of 165 runners.

Yet very quickly, it became apparent that pre-race prognosticators who had foreseen a second Oksanen vs. Kelley duel were being proven correct. Both runners looked composed and strong, with Kelley taking an early lead and setting a higher tempo to whittle down potential challengers.

Joining the duo was a dwindling group that included Englishman Fred Norris, a 39-year-old veteran of multiple Olympics. Norris’s unusual journey had taken him from a split life as a coal miner and distance runner in his home country to U.S. college McNeese State in his late 30s (as he sought a way to become a coach while still doing some competitive running). Norris was in good form, and stuck to the leaders’ pack in the hope of upsetting the two favorites.

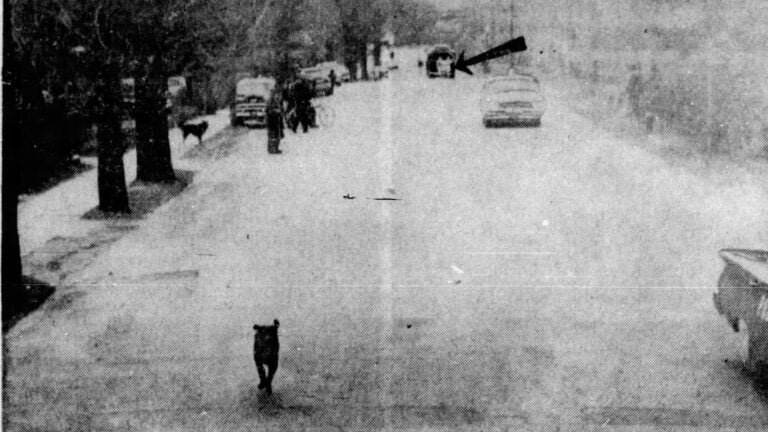

The drama continued to escalate, especially when most surprising member of the leading group joined approximately around Mile Six.

A “floppy-eared, mongrel dog” (per the description of D. Leo Monahan of The Daily Record) jumped in to run with the pack, leading them as a would-be pace-setter. The dog was described as possibly being a black Labrador retriever, though accounts differed.

For a seemingly impossible distance of roughly 10 miles, the dog happily led the Norris-Oksanen-Kelley group. Then, as the trio approached the fatefully-named Lower Newton Falls, disaster struck.

According to Sports Illustrated’s Gwilym Brown, the dog suddenly “swerved from the left side of the road and into the runners. Oksanen jumped to avoid him, but the dog hit Kelley full across the legs and he went down violently.”

“An instinctive act which marked him instantly as a great gentleman”

Collapsed in a heap on the ground, it looked for a moment as if the race was over for Kelley. But as if in answer to the already improbable circumstances of a dog playing a central role, another completely unexpected event occurred. Norris stopped to help his competitor.

“Norris did an instinctive act which marked him instantly as a great gentleman,” wrote Nason. “The 39-year-old alumnus of the British coal mines stopped, turned back, and helped the floundering Kelley to his feet.”

“It happened so fast,” Norris later told Brown. “I hardly had time to think. [Kelley] looked as if he was down to stay, and he’d been running such a good race. So I grabbed him and shouted, like a command, ‘Get up!’ It snapped him out of the shock, and he was running right away.”

Oksanen, who had successfully hurdled the dog, continued unimpeded.

“He did not even turn his head to see what damage he been wrought by the canine twister which struck the threesome,” Nason explained. But thanks to Norris’s help, Kelley — adrenaline pumping — surged back into the race and quickly caught up to the Finn.

Unfortunately for the Englishman, the act may have cost him. Having broken his concentration, and combined with the extra exertion right before the Newton hills, Norris suffered in the ensuing miles and fell back from the two leaders, eventually finishing third.

“Did you ever see a dog in such good condition?”

Kelley, having regained his pre-fall status as the race leader, navigated most of the remaining course with Oksanen once again tucked just off his shoulder.

It wasn’t until the runners were less then a mile from the finish that Oksanen made his move.

“It was directly at Charlesgate West, with 1,000 yards to journey, that Oksanen reached down into his physical resources and pulled forth a weary sprint,” Nason recounted.

Oksanen, as he had done in 1959, overcame Kelley right near the end.

The Finn “simply had too much power for me at that stage,” Kelley admitted. For the fourth time, Kelley finished in second place (he would total five second-place finishes during his distinguished Boston career).

Obviously, the dog dominated post-race discussion. Oksanen, sympathetic to Kelley, took a harsh line.

“Kelley’s a tough man to beat. They should have shot the dog that knocked him down,” he told reporters.

But despite Oksanen’s words, Kelley — himself a dog owner — was entirely sympathetic.

“Falling was a little shock, made the adrenaline run a little faster, but it didn’t cost me the race,” he told the Globe’s Harold Kaese. “He wasn’t a vicious dog. He was just having fun and was sorry when I fell. Did you ever see a dog in such good condition?”

Later, Kelley again took the dog’s side against critics.

“He was a such a happy, spirited dog, and he seemed to be having such a good time.”

The other thing Kelley recognized after the race — aside from crediting Oksanen’s strength — was the conduct of Norris for helping him up after the fall.

“What a tremendous act of sportsmanship,” he said of the Englishman. “Fred broke his racing rhythm and may have thrown away his chances of winning to do what he did.

“I wonder, had the situation been reversed, if I would have done the same for him? I like to think I would—but in the heat of a hard foot race you’re tempted to say, ‘Well, those are the racing breaks.’”

As for the dog, it was never properly identified.

“Unfortunately,” remarked Kaese, “[Boston Marathon race director] Jock Semple shooed the dog from the scene of the crime with Scottish imprecations, without thinking to get a nose print.”

Sign up for the Today newsletter

Get everything you need to know to start your day, delivered right to your inbox every morning.