“The women in this party are so assertive now that we may need some special rules for men to get them pre-selected”.

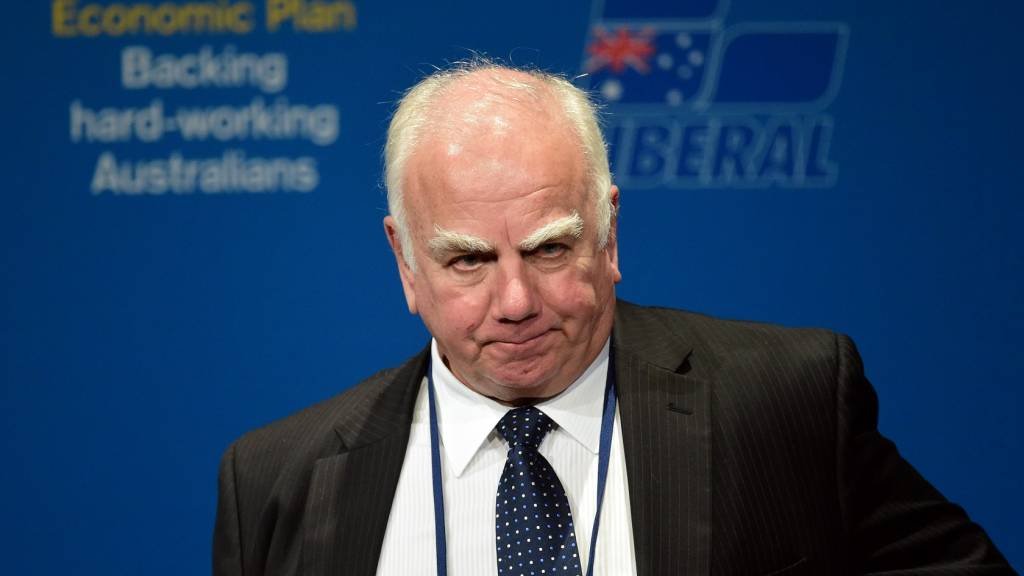

For a man with more square centimetres of eyebrow than there are federal female Liberal MPs, Alan Stockdale — showing the fine political antennae of someone last in active politics in the 20th century — sure knows how to upset people. Female people, particularly. The kind that aren’t found very much in his party. The kind that make up the NSW Liberal’s Women’s Council, to whom he made his hilarious jape.

Stockdale knows a thing or two about avoiding girl germs. In the last Kennett cabinet, of which he was treasurer, there were four women out of 20. Count ’em. When he finished up as Liberal president in 2014, he urged that there be more women in senior roles within the party, but rejected quotas. At the time, the Abbott cabinet had one woman.

One word in his ill-judged remark was especially poorly chosen: “Assertive”. Nothing, except rolling out “hysterical”, could have been more finely calculated to convey the image of a pale, male and stale reactionary being discomfited by uppity women who won’t stop talking. Sussan Ley rightly responded that she wanted more assertive women to join the party.

Stockdale, along with his fellow Victorian and successor as federal president Richard “Skeletor” Alston, are two of the gang of three imposed on the NSW Liberal division by Peter Dutton in the wake of the NSW party’s local election debacle. That imposition was resented by NSW moderates at the time and, now that Dutton has been dispatched into the outer darkness, is seen as the persistence of a very dead hand from well beyond the political grave — and one located in that graveyard of Liberal hopes, Victoria.

The problem for Liberal women, however, is that Stockdale was expressing, allegedly in jest, exactly what large numbers of old white male Liberal members think: that it’s high time everyone stopped talking about the rights of women, and people of colour, and trans people, and people with disabilities, and focused on their rights, instead.

Resentment is the fuel that powers the base of the Liberal Party, which like any party membership is more extreme than its parliamentary ranks. Resentment toward anyone not white and male, especially. It’s why fostering, and exploiting, resentment has been so appealing to Liberal leaders, Malcolm Turnbull aside, since the Howard years. It’s why Peter Dutton became leader, with the confident hope he could masterfully exploit resentment to throw Labor out. He was successful in defeating the Voice referendum, which became a vote for maintaining white privilege, but resentment can only get you so far in a cost of living election. Money goes a lot further, as Anthony Albanese demonstrated.

That old white membership is the single biggest impediment to the Liberal Party ceasing to look like a political documentary about the 1970s and looking more like Australia a quarter of the way through the 21st century. Urban Australia, with high numbers of voters born overseas, a more diverse array of economic activities, and a reliance on two-income households and thus working, often professional, women, is fast becoming unknown land for the Liberals. They can’t get elected there, and they don’t look anything like the electorates they’re pursuing.

The dearth of women and people of colour in Liberal ranks is just one part of a broader talent problem for the Liberals. Being out of office for extended periods has real impacts on a parliamentary party. Not merely do experienced former ministers move on, to be replaced by novices, being in opposition disrupts the supply chain of future MPs, who are disproportionately drawn in all parties from the ranks of former staffers. Oppositions have far fewer staffers than governments; long stints in opposition reduce the talent pipeline.

In its spells in opposition, Labor has been able to rely on success at the state level, and even local government, to keep providing the training ground for political staff and future MPs. The Liberals face an extended period being in office only in Queensland, depending on the outcome of events in Tasmania.

This impact of stints in opposition shouldn’t be underestimated: the first Howard term was chaotic and reflected that the Coalition had been out of power for 13 years. Labor’s first term in office after Howard’s 11-year term was even worse. Anthony Albanese was fortunate in being able to draw on a large number of ex-ministers who’d served under Rudd and Gillard when Labor returned to power in 2022. By the time the Coalition returns to office, there might have been a complete turnover of talent.

And whether that new array of talent includes significantly more women than now will depend partly on whether party pragmatists can eliminate the Stockdale Syndrome within the membership and begin the task of bringing the Liberals into the early 21st century.

What is the root cause of the Liberal Party’s women problem — and can it be fixed?

We want to hear from you. Write to us at letters@crikey.com.au to be published in Crikey. Please include your full name. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.